Fellwanderer

The story behind the Guidebooks

Fellwanderer was published in October 1966 with a dedication:

“To Fellwanderers past, present and future”

<<>>

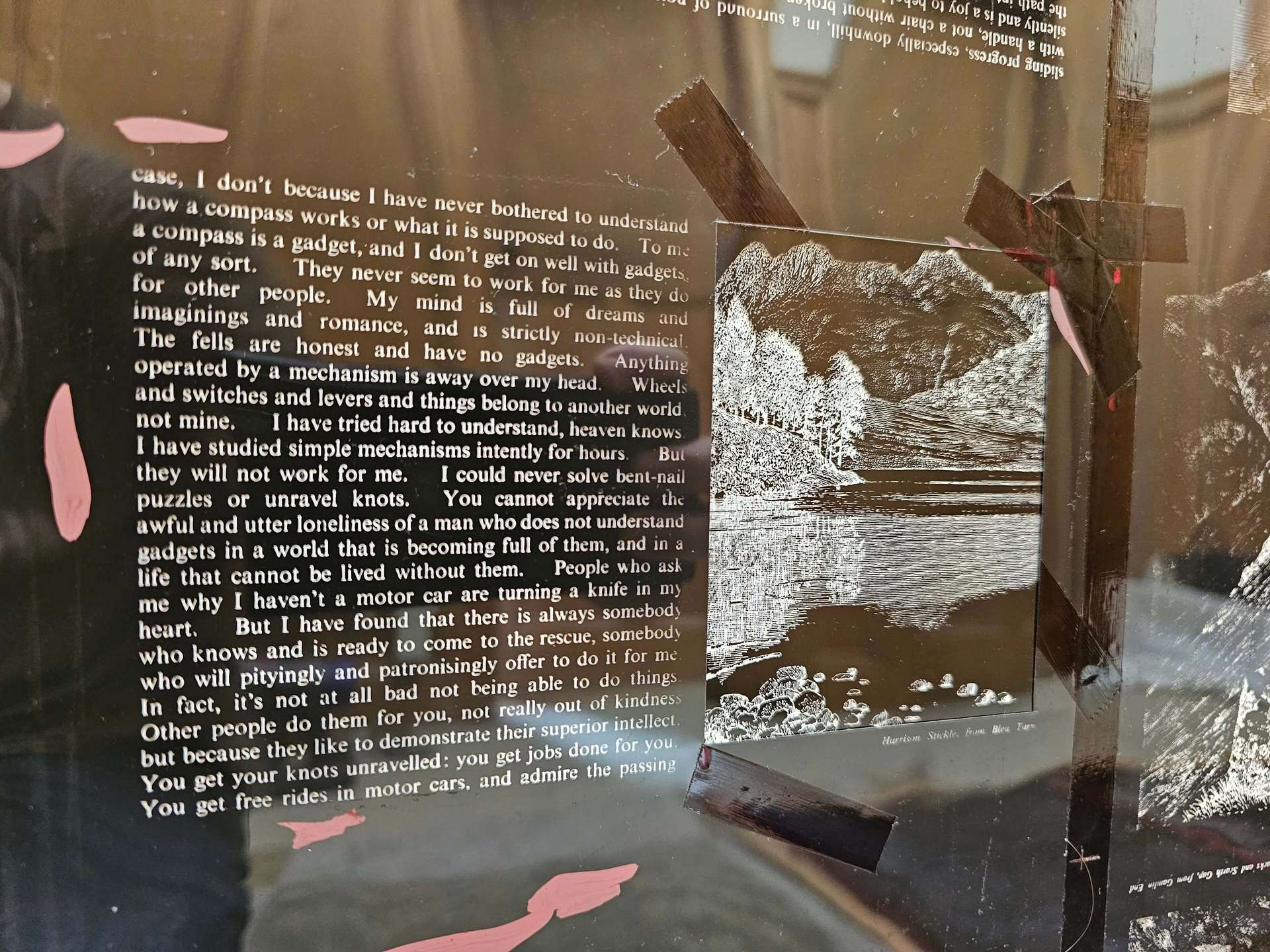

Wainwright crafted the narrative for his subsequent project even before the release of The Western Fells. Titled Fellwanderer, this work serves as a compendium of essays and reflections drawn from his immersive experiences traversing the Lake District fells. An integral component of his expansive Pictorial Guide to the Lakeland Fells series, Fellwanderer not only encapsulates Wainwright’s contemplations but also presents an array of sketches and photographs showcasing the landscapes that held a special place in his heart. In essence, this collection emerged as an invaluable insight for both his ever-expanding and inquisitive fanbase and those with a profound interest in the inherent allure of the region and the joys of outdoor exploration.

The book provides a captivating glimpse not only into the intricacies of the guides but also into the persona of Wainwright himself. Despite being a notably private individual, he extends a certain degree of openness, unveiling facets of his life. Despite the widespread acclaim that Fellwanderer received, it did not escape criticism. A notable source of dissatisfaction among Wainwright’s readers stemmed from their preference for his characteristic handwritten text and route drawings, which had become a familiar and cherished element over 13 years. Additionally, a few individuals took issue with some of Wainwright’s viewpoints, perceiving them as overly critical.

It’s unlikely that those who gave unfavourable reviews to this book were ever destined to become long-term disciples of Wainwright. Fellwanderer merely marked the beginning of Wainwright’s literary journey. Those who found his opinions occasionally stern would soon realise that these critiques were mild compared to what awaited in Ex-Fellwanderer, published over two decades later. Personally, Fellwanderer stands as one of my favourite books, offering an in-depth history of the guides, a perspective that was previously absent. If there were one alteration I could propose, it would be to have the book formatted as a guidebook, allowing it to seamlessly complement the seven Pictorial Guides as their devoted companion.

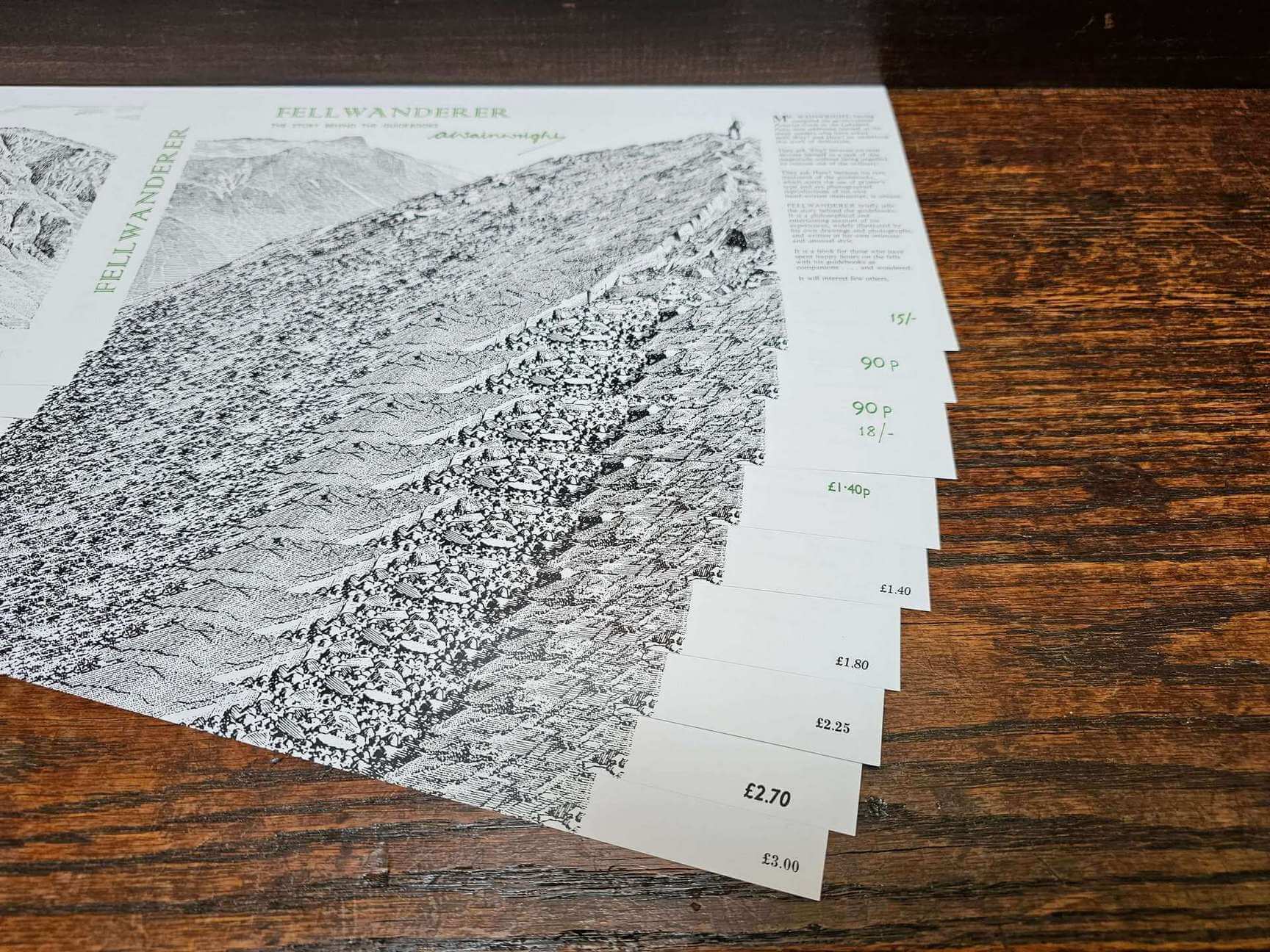

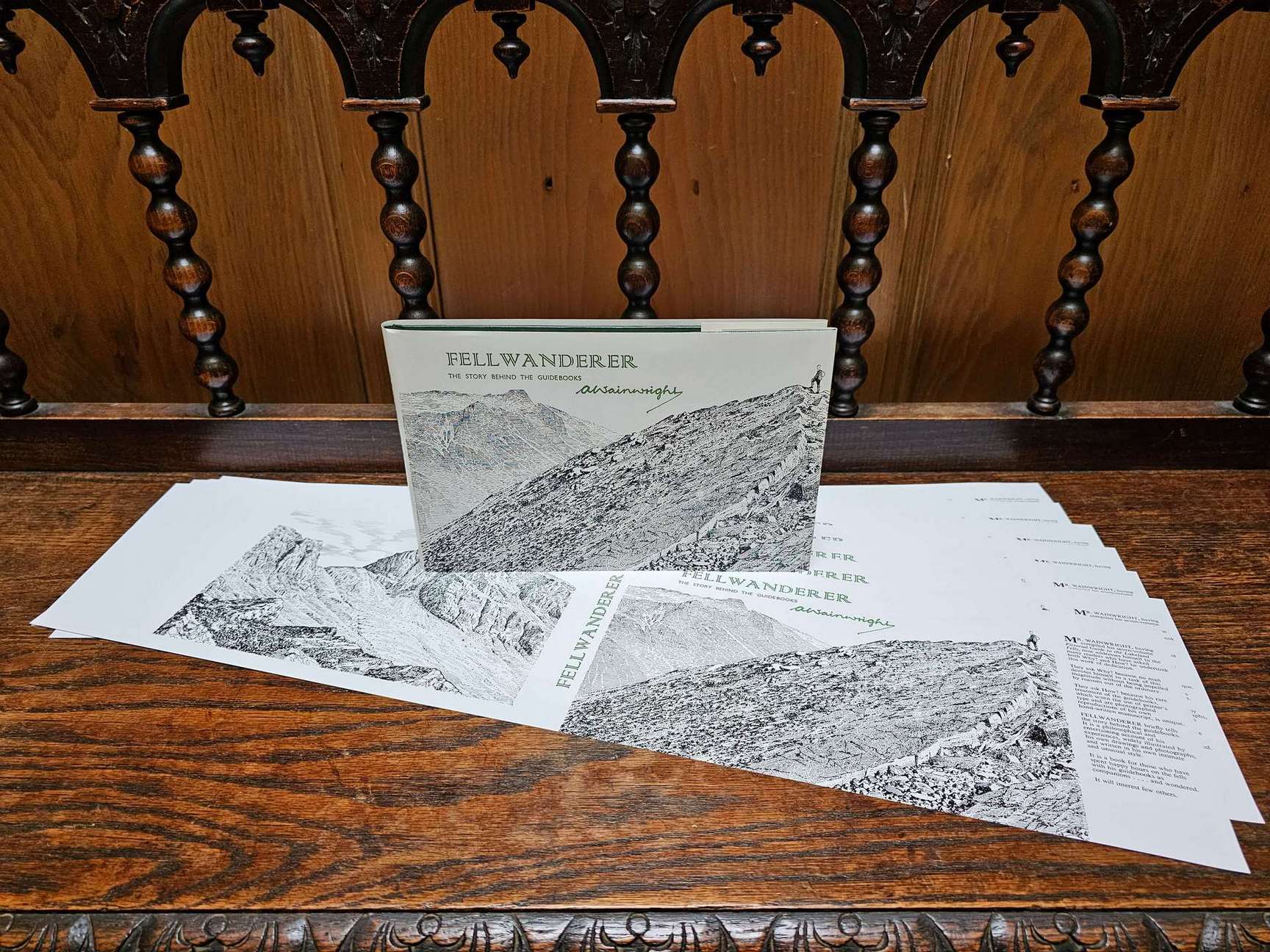

Fellwanderer debuted through a leaflet strategically inserted by Harry Firth, the General Printing Manager at the Westmorland Gazette, within the initial copies of The Western Fells. Priced at a modest 15/-, the book garnered reasonable sales. The announcement of Wainwright’s new title was not confined to the leaflet but also found a prominent place in Cumbria magazine, complemented by a half-page advertisement in November 1966.

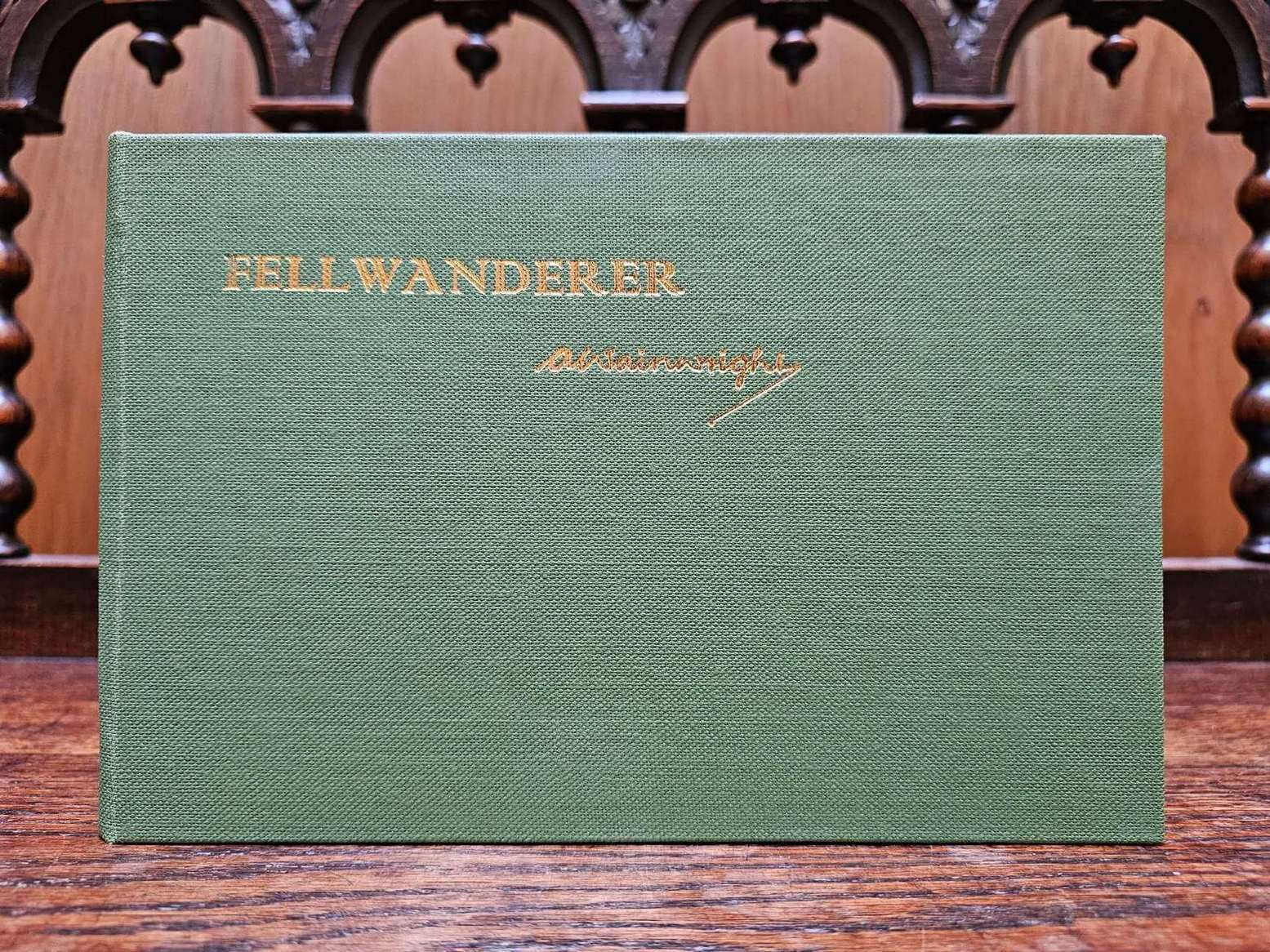

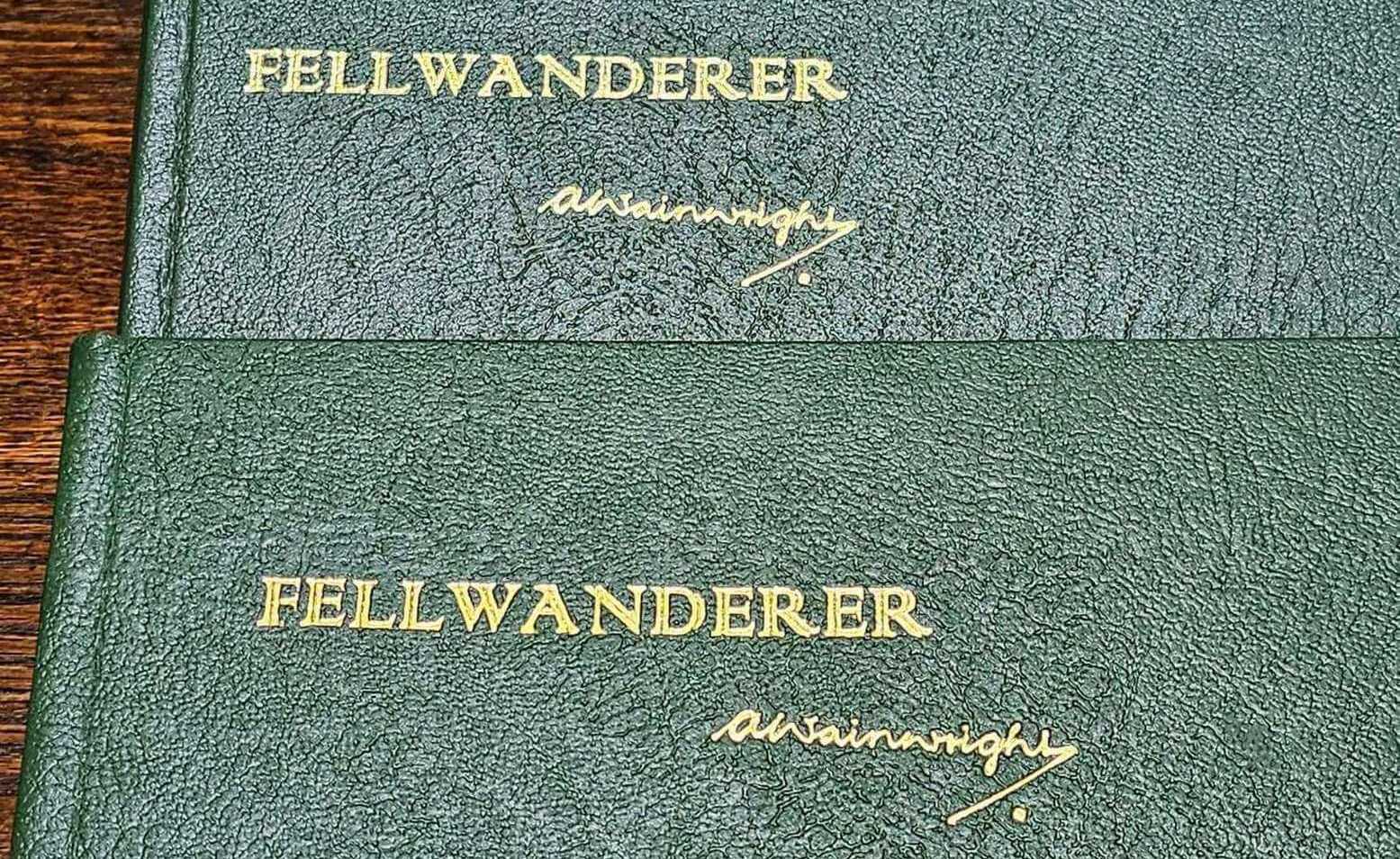

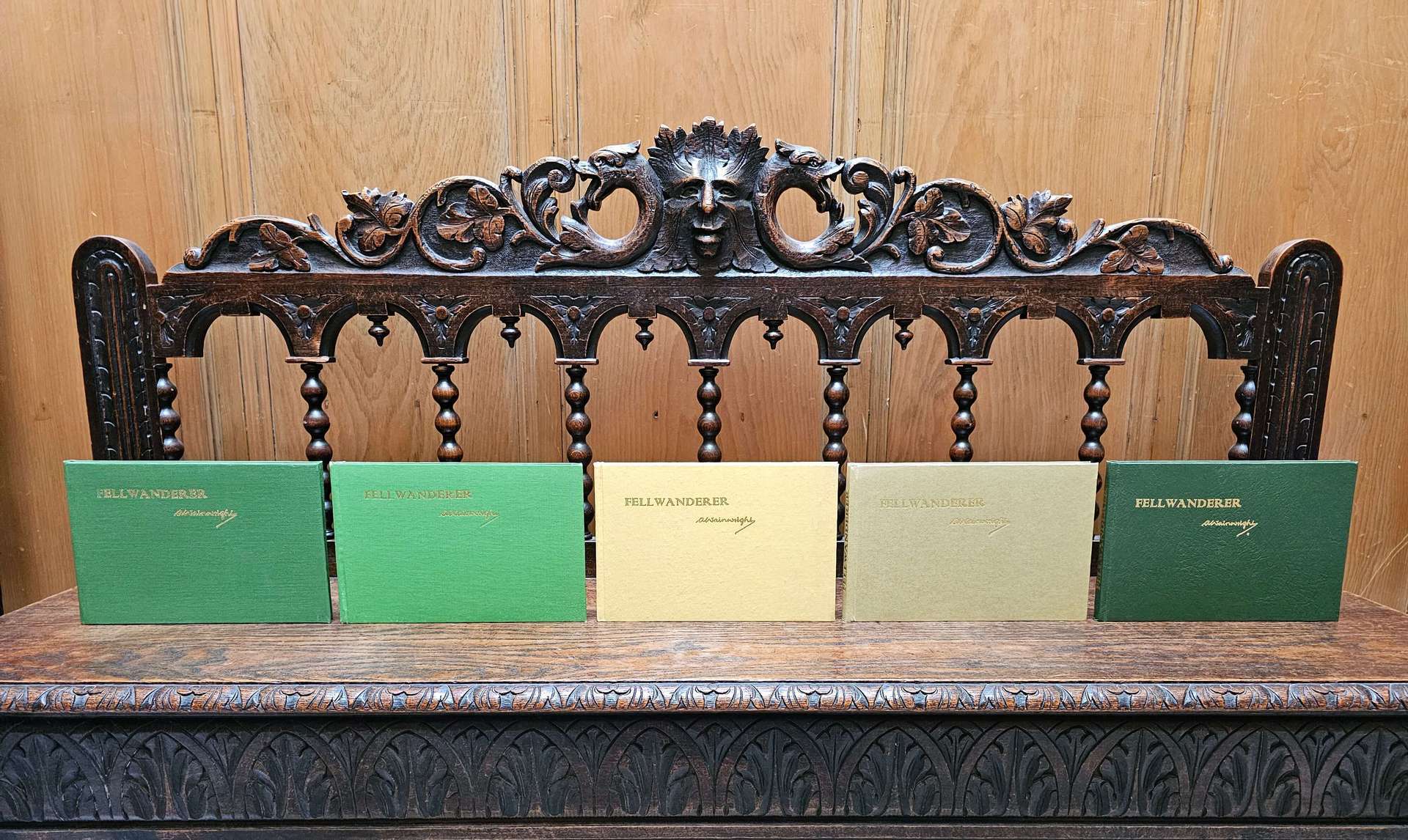

The book spans 128 pages and adopts a distinctive landscape format encased in a premium green cloth binding. The front and spine are embellished with gold blocking, adding a touch of elegance. Interestingly, the distinguishing characteristic of a First Edition lies in a spelling mistake. Discerning between a First Edition and subsequent impressions without this particular error becomes impossible, given that the second impression replicates the first edition in every aspect.

To identify whether your copy is a First Edition, examine the description of the last photograph at the book’s rear. If it spells “Gatescarth” (the correct spelling being “Gatesgarth“), then you indeed have a First Edition. The misprint was rectified in subsequent print runs. Credit goes to Derek Cockell for bringing this error to light several years ago.

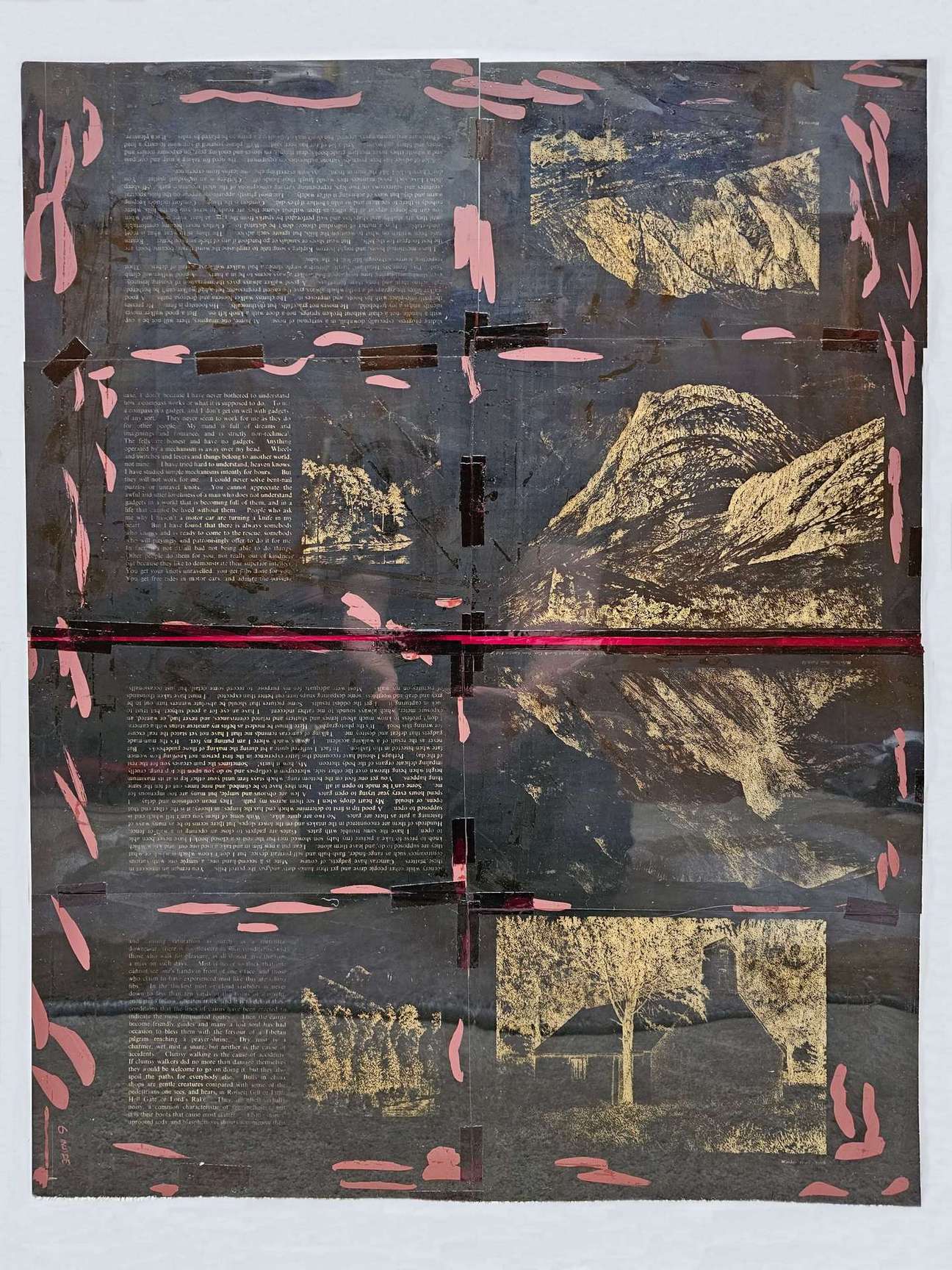

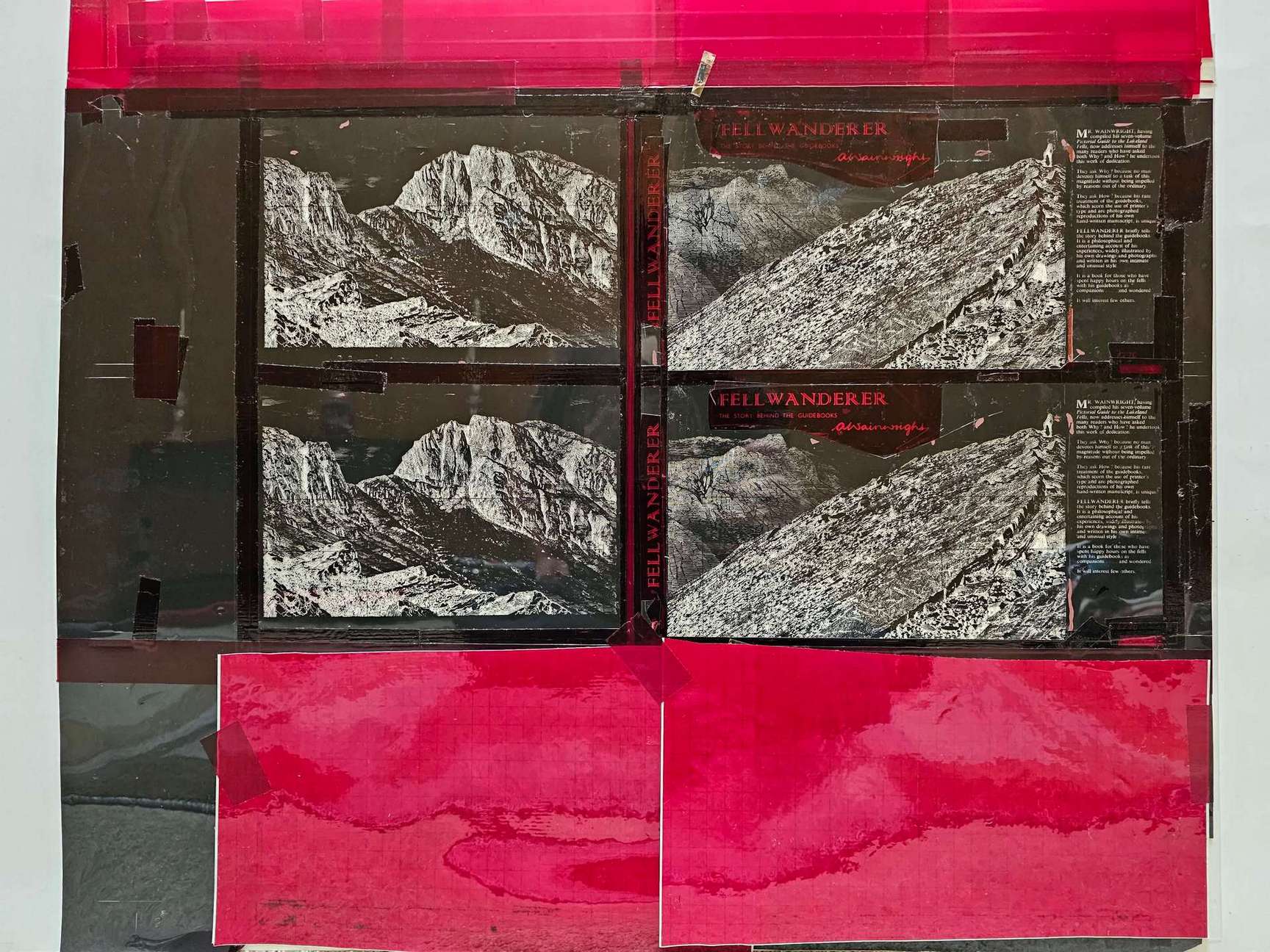

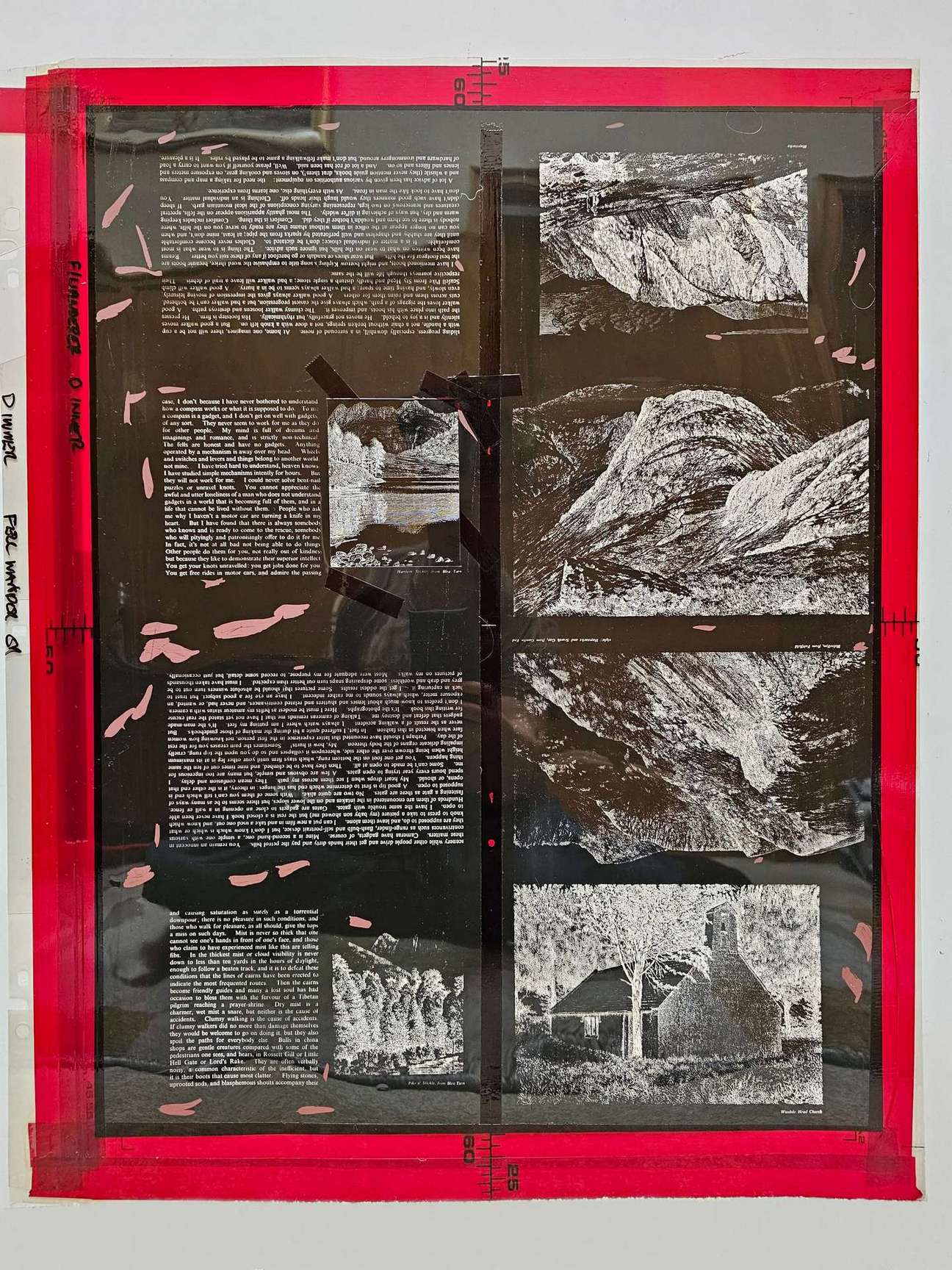

In 2019, I had the good fortune of discovering the original 1966 Westmorland Gazette printing negatives for Fellwanderer when I assumed the custodian role for all existing Wainwright book printing materials. Despite showing signs of wear, these negatives had managed to withstand the passage of time, revealing a surprising resilience. It was evident that they had remained untouched and unused for several decades.

Determining the print date of certain copies of Fellwanderer can be difficult for those not well-versed in Wainwright’s works. The absence of impression numbers or a list of recently published books adds complexity. Each copy bears the original publication date of 1966, potentially misleading readers into thinking their copy is a First Edition.

Fortunately, the case material and pricing of Fellwanderer align precisely with the guidebooks. Prices saw incremental increases throughout the 1970s, culminating in a printed dust jacket price of £3.00 in 1981. Between 1982 and 1991, price stickers were utilised. An additional distinctive feature is the removal of gold blocking from the front of the book in 1980, serving as a helpful identifier for the printing period.

The gold blocking process was manual, with the book title and Wainwright’s signature engraved on a single block, allowing for a single stamp on the case. This uniform gold blocking persisted for the majority of its usage period. However, inconsistency was observed in the final copies featuring gold blocking. The signature was inconsistent on each copy, lacking parallel alignment with the book title. The anomaly suggests that around 1979, approximately two separate blocks were employed before the gold blocking practice was ultimately discontinued. The reason for this change remains unclear.

Over the years, the original negatives for Fellwanderer experienced deterioration, particularly in photo quality, which steadily declined throughout the 1970s. Eventually, recognising the need for improvement, the Gazette produced new negatives. This involved the creation of new artwork and the comprehensive re-scanning of all of Wainwright’s original photos. Although a colossal undertaking, the completion of this project marked a significant increase in print quality.

After obtaining the new artwork in 1980, an intriguing aspect emerged—the choice of paper for mounting the artwork in preparation for photography. Interestingly, the Gazette did not opt for new paper; instead, they repurposed ‘previously printed’ sheets initially used for other customers, showcasing a resourceful approach to materials.

These repurposed sheets, sourced from a 1980 calendar, provided a unique marker. The leap year was explicitly noted in February, and the date was confirmed. In a curious twist, I came across an article in the calendar attributed to John Halfacre, the President of the Athletic Union at Lancaster University. The intriguing question surfaced: Was John Halfacre aware, or would he even care, that his name adorned the back of each sheet of original artwork for one of Wainwright’s most renowned publications?

Given that 43 years had passed since the calendar’s creation, the question arose: where was John now, and could I find him? Driven by curiosity, I embarked on a search and promptly located him. A phone conversation ensued, during which John expressed sheer delight upon learning that his past University work adorned the back of Wainwright’s Gazette artwork. After sending him a scan, memories of the calendar returned to him as if it were yesterday. John was genuinely pleased that I reached out to share this unexpected discovery.

Completing the new negatives marked a substantial improvement in the quality of all subsequent reprints, particularly the photos. However, these changes came with a drawback—while the drawings were slightly enhanced from the original negatives, they fell short of perfection. The only viable solution was to embark on the task of re-scanning Wainwright’s original illustrations. This, however, posed its own problems, as locating all the originals proved impossible. Over the years, most of them had been sold for charity, with only a handful featured in Fellwanderer and appearing in his other publications.

Starting in 1988, the Gazette transitioned into a publisher-only role, and the responsibility for book printing shifted to Titus Wilson & Son Ltd. This arrangement persisted for three years until 1990 when the printing was relocated again, this time to Titus Wilson & Son (a different printer under the same name). See The Gazette Prints its Final Book for the whole story.

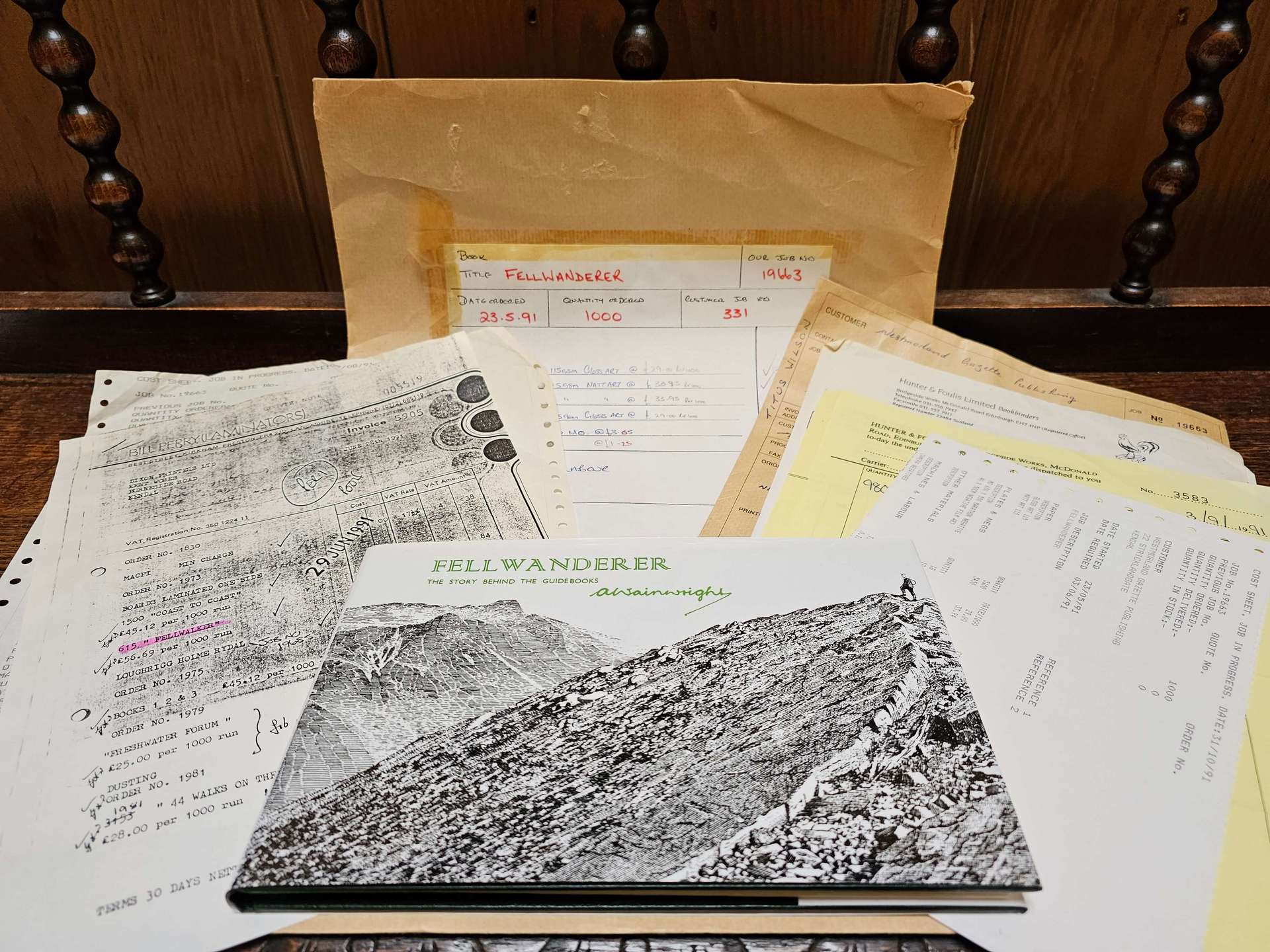

An urgent order for 1,000 copies of Fellwanderer was authorised by Andrew Nichol, the General Printing and Book Publishing Manager, on May 23, 1991. Regrettably, this marked a poignant moment as this title’s last order. Since then, Fellwanderer has not been reprinted.

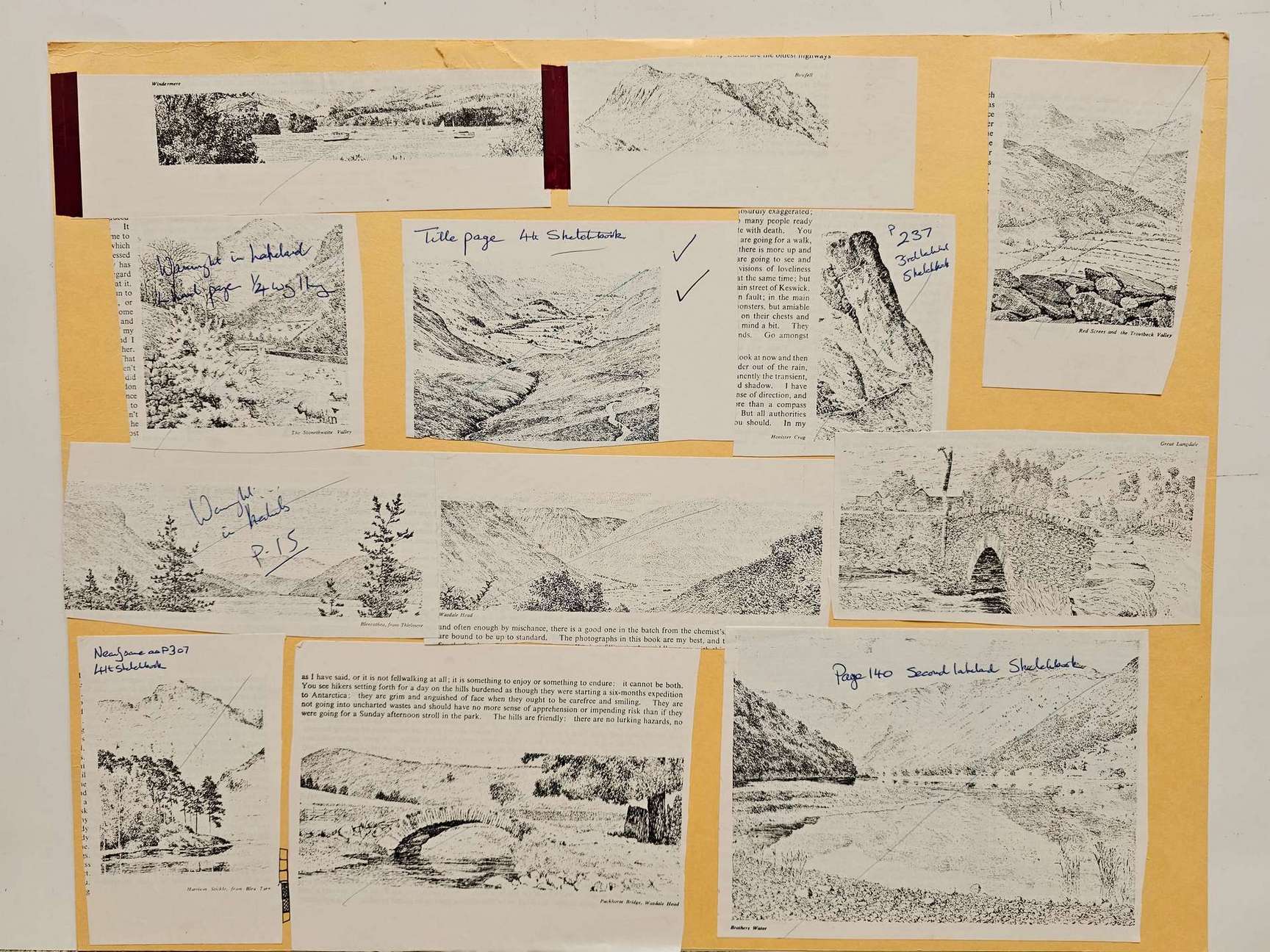

For the final book order, the Gazette sought to address the issue of faded drawings in Fellwanderer. While twelve were earmarked for replacement, only the six most severely affected were ultimately swapped. Four were direct replacements found in the Lakeland Sketchbooks and Wainwright in Lakeland. The remaining two drawings represented alternative depictions of the same mountains.

These substitutes were:

1. Harrison Stickle. The original is held in the Kendal County Archive but wasn’t there in 1991. The alternative drawing was taken from A Fourth Lakeland Sketchbook.

2. Honister Crag. The alternative was taken from a Third Lakeland Sketchbook. I have since found the original like-for-like drawing in Wainwright in Lakeland, perhaps overlooked at the time.

The faded drawings, initially replicated from the ageing 1966 negatives, were excised from the 1980-produced negatives and substituted with these new scans. Interestingly, the introduction of two alternative mountain drawings went largely unnoticed. It wasn’t until 2019, during a thorough examination of all the printing materials, that I became aware of these subtle but significant changes.

Upon discovering the alterations in Fellwanderer, my quest for a copy from the final print run spanned nearly a year. When I finally secured one, my enthusiasm was dampened by discovering several torn pages within. My pursuit for a replacement copy persisted for another two years, yielding no success. Fortunately, a friend, John Fearn, came to the rescue with a spare copy from 1991. I owe John a tremendous debt of gratitude; without his assistance, my search might still be ongoing.

<<>>

It’s surreal to contemplate that over three decades have passed since Fellwanderer was last in print. Although it is a product of its time and might not resonate with the masses today, it’s reassuring that copies are still readily available for those who appreciate its significance.

Numerous memorable moments punctuate the pages of this book. I hope the woman Wainwright briefly encountered on High Stile in July 1964 acquired a copy and recognised herself in the passages where he spoke about their encounter. Such a realisation would undoubtedly have made her day memorable and confirmed her astute guess that she had indeed crossed paths with the renowned Wainwright.

The book closes with one of Wainwright’s finest passages that still resonates with fellwalkers today:

Every day that passes is a day less. That day will come when there is nothing left but memories. And afterwards, a last long resting place by the side of Innominate Tarn, on Haystacks, where the water gently laps the gravelly shore and the heather blooms and Pillar and Gable keep unfailing watch. A quiet place, a lonely place. I shall go there for the last time, and be carried: someone who knew me in life will take me and empty me out of a little box and leave me there alone.

And if you, dear reader, should get a bit of grit in your boot as you are crossing Haystacks in the years to come, please treat it with respect. It might be me.

Back to top of page