Wainwright and i

Guest article by George Kitching

On leaving school, if you had told me a staunchly conservative old curmudgeon who loved to smoke a pipe and ramble up hills would become one of my absolute heroes, I would have laughed out loud. I wasn’t into mountains, you see. I was into guitars, and while I had grown up in the country and absorbed, by some kind of unconscious osmosis, a love for nature and the outdoors, it was lying dormant. What I craved was a city. One with a vibrant music scene, where I could form a band and spend nights playing in smoky, sweaty clubs.

I secured a place at Newcastle University, but deep down, my studies played second fiddle to my musical ambitions, even if those ambitions far outstripped my abilities. My first bands were hardly likely to set the world alight, but by 1990, I had honed my skills and met people with just the right mix of creative chemistry. We formed a new band called HUG, and things were immediately different. Songs took on their own life; our sound grew into something more than the sum of its parts, and people started to sit up and listen. A year later, the NME named us as one of their top tips for 1991, and it really did seem as if anything was possible. But while others on the list sailed into the arena of international stardom, our transit van stalled at the perimeter, performed a three-point-turn, and deposited us back at the Gateshead DHSS, where our hopes of avoiding more gainful employment were unceremoniously quashed.

I retrained in IT, and when my wife was offered a dream job in Cumbria, I urged her to take it. I set about looking for opportunities for myself. Eventually, I secured a position with a company making clinical software for managing people on dangerous drugs (the prescribed, not the proscribed kind).

Our first house was on the edge of a wood, right out in the wilds. Until then, I had never really understood the term “the roaring silence.” When you live in a city for any length of time, you cease to hear the constant hum of traffic. Yet, it is always there, a comforting reminder that everyday life rumbles on outside the window. Having that removed was unnerving. I would lie awake at night, acutely aware I could hear nothing. When a barn owl screeched like a banshee, I nearly shot through the ceiling, and later, when I heard the bark of a roebuck for the first time, I thought the Hound of the Baskervilles was coming through the wood.

But the countryside soon began to weave its magic, and before long, I lifted my eyes to the hills. A visit to Haweswater lit a fuse. We were standing on the shore, looking across at the magnificent crags of Riggindale Edge rising to the long whaleback of High Street, when my friend Lucy told me a Roman road used to run over it. It seemed so improbable; I was dumbfounded, but I knew immediately that I had to go up there. I bought a Landranger guidebook specifically because it included that walk, and a few weeks later, I made the ascent.

It was a strange, fresh and exciting time but tinged with a sadness I couldn’t permit myself to admit. What we’d had in HUG was special. Not only had we clicked creatively in a rare way, but we’d become incredibly close—a family. Now, not only had I given up on a dream, but I’d flown the nest. Of course, all that was offset by the buzz of the new. I was embarking on a new chapter with my soulmate in the most beautiful places. For the first time, I had pay and prospects. I was discovering skills I didn’t know I had, helping develop software which could assist in preventing strokes. I felt useful. But something was missing. That other side of me: the useless, romantic, creative one; the one that could literally lose himself for hours in a daydream or hear eternities in the warm oscillations of a guitar chord; that side still needed space to breathe. When I first set foot on High Street, I immediately knew I had found it.

At the age of twenty-three, Alfred Wainwright boarded a coach from Blackburn to Keswick with his cousin, Eric. It was his first holiday in Lakeland (his first holiday anywhere). That afternoon, they climbed Orrest Head and witnessed the fells for the very first time. It was an experience Wainwright described as “magic,” a revelation so unexpected that I stood transfixed, unable to believe my eyes.” The very next morning, the pair set off for Troutbeck to climb High Street via the flank of Froswick and the summit of Thornthwaite Crag—because Wainwright, too, had been intrigued to learn of the Roman road.

None of this meant anything to me at the time. I still didn’t really know who Wainwright was, but Riggindale Edge had taken my breath away figuratively and literally. The panoramic vistas over Haweswater, the rugged cliffs that encircle Blea Water, and the final exhilarating scramble up the Long Stile had left me hungry for more, so when my guidebook described Blea Water and Rough Crag as reminiscent of Red Tarn and Striding Edge, I set my sights on Helvellyn.

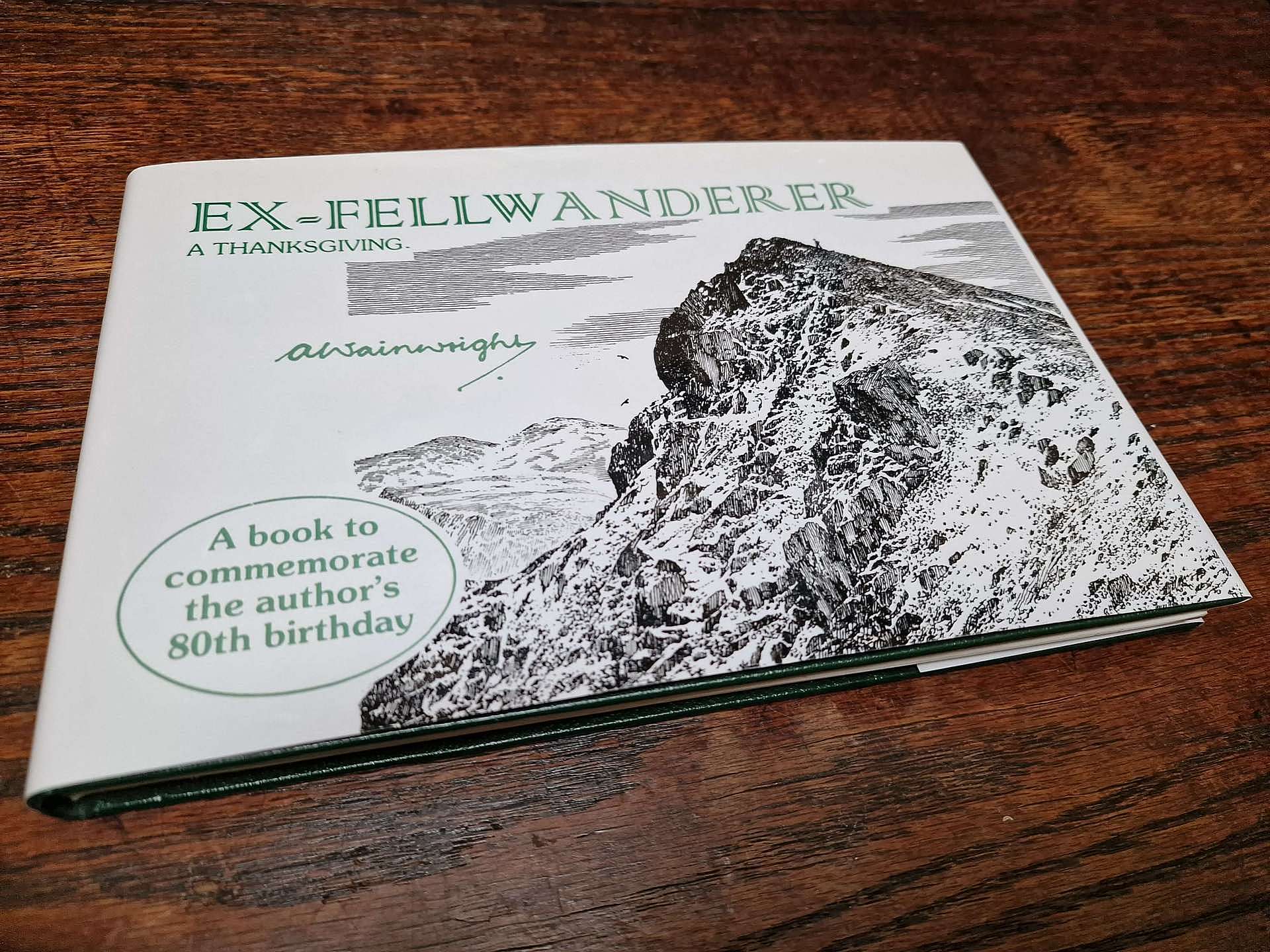

Years later, I would read Ex-Fellwanderer and discover that Striding Edge was where Wainwright and his cousin headed next too:

“Before reaching the gap in the wall, we were enveloped in a clammy mist, and the rain started…We went on, heads down against the driving rain, until, quite suddenly, a window opened in the mist ahead, disclosing a black tower of rock streaming with water, an evil and threatening monster that stopped us in our tracks. Then the mist closed in again, and the apparition vanished. We were scared: there were unseen terrors ahead. Yet the path was still distinct; generations of walkers must have come this way and survived, and if we turned back now, we would get as wet as we would by continuing forward. We ventured tentatively and soon found ourselves climbing the rocks of the tower to reach a platform of bare rock that vanished into the mist as a narrow ridge with appalling precipices on both sides. There was no doubt about it: we were on Striding Edge.”

The weather was kinder to me when I first set foot on Striding Edge; I now knew who Wainwright was. His name had come up in passing when I mentioned to people that I was interested in doing some fellwalking, but it hadn’t really stuck. That changed after visiting Kendal Museum, where our friend, Meriel, was the curator. Meriel’s maiden name was Wainwright, and when Sandy and I arrived, she was deep in conversation with an outdoorsy-looking couple, explaining that “no, she wasn’t related to him.” She then guided them to a display case containing a pair of Wainwright’s boots, his pipe, and a pair of his old socks (socks!). The couple stared misty-eyed at these artefacts as if they were religious icons. I was intrigued. A few days later, in the Carnforth bookshop, I found a secondhand copy of his Pictorial Guide to the Southern Fells and snapped it up to see what all the fuss was about.

The book was a little battered and well-thumbed, and the annotations in biro suggested it had visited the summits it described. It was unlike any guidebook I’d ever seen. In place of OS maps, there were a series of hand-drawn sketches, part map, part illustration, which seemed to render the whole essence of a mountain on a 2D page with an admirable economy of line. Devoid of the usual tips about parking, refreshments, and toilet facilities, the accompanying text was nothing short of heartfelt poetry. It spoke volumes in a few simple paragraphs shot through with warmth, humour, passion and practical advice. Often from below, with clouds draping the tops and echoing the shapes of the summits, the mountains can appear in a different realm, more of the sky than of the earth. The Southern Fells seemed like the arcane scriptures of a sage, unlocking the key to their mystery.

I explored the Coniston Fells, Scafell Pike, Great Gable, Crinkle Crags, Haystacks, and the Langdale Pikes. Then we bought a house near Cartmel, and what with moving and decorating, work, and everything else life puts in the way, my excursions into the fells dwindled to the occasional foray. And they remained that way for the next fourteen years. Then, Storm Desmond flooded the gym I used to frequent and forced me to look for another way to keep fit. Remembering how much I had loved fellwalking, I bought a new pair of boots, tried them out on Helm Crag, and never looked back. Suddenly, any weekend that didn’t include a fell walk was a rarity and left me yearning to return to the hills.

I invested in the complete set of Pictorial Guides, and as my interest deepened, I felt a compulsion to revisit Haystacks—this time to pay my respects. It is, of course, where Wainwright’s ashes were scattered.

“All I ask for, at the end, is a last long resting place by the side of Innominate Tarn, on Haystacks, where the water gently laps the gravelly shore and the heather blooms and Pillar and Gable keep unfailing watch.”

Wainwright described Haystacks as standing “unabashed and unashamed amid a circle of higher fells, like a shaggy terrier in the company of foxhounds”. Its summit is a veritable Shangri-La of tiny tarns, rocky turrets, and heather-clad plateaux grazed by Herdwicks. Serendipity smiled on me that day and gave me Innominate Tarn to myself. I sat by its tranquil waters and reflected long on my journey and Wainwright’s part in it. He made a strange bedfellow for Jimi Hendrix and Pete Townshend, but unquestionably, he had become just as much of an inspiration.

Later, as I neared the bottom of Fleetwith Edge, I caught sight of a small white cross low on the fell side. It marks where Fanny Mercer fell from Fleetwith Edge in September 1887. Her simple memorial is a sobering reminder that the fells can be treacherous and beautiful. It’s heartbreaking to think one so young was robbed of her life on what should have been a joyful excursion. Tragic accidents occur daily, some of a much greater magnitude than the century-old story of a servant girl from Rugby. And yet this simple cross remains affecting because there’s no objective yardstick for pain. That whole communities are devastated by fire, flood, disease, or famine doesn’t negate the suffering of someone bruised by a failed relationship or grieving the loss of a loved one. We all have our crosses to bear, however big or small, but ironically, it’s often hardship that sharpens our senses of the beauty in the world. The most affecting songs are rooted in heartbreak, and perhaps the pain of a loveless marriage led Wainwright to find hope, inspiration, and validation among these hills.

“The fleeting hour of life of those who love the hills is quickly spent, but the hills are eternal. Always there will be the lonely ridge, the dancing beck, the silent forest; always there will be the exhilaration of the summits. These are for the seeking, and those who seek and find while there is still time will be blessed both in mind and body.”

I completed the Wainwrights on Catstycam, carrying a large, painted cardboard cutout of a pipe, replete with a puff of smoke bearing the magic number 214–my wife’s artistic contribution to my endeavour. When a party of young people arrived on the summit, one lad came over, curious about the pipe. He’d heard of Wainwright and wanted to know more. When I fished out my copy of The Eastern Fells, he stared transfixed at the pages, just as I had done in the Carnforth bookshop all those years before. When they readied to leave, he turned to me and said, “I’m going to get that book. I’m going to get all of them.” I felt like I had passed on a piece of magic.

Yet, the place I feel closest to Wainwright is not Catstycam, nor even Haystacks, but Scafell Crag. When viewed from Mickledore or the West Wall Traverse, it is grand, majestic, and overwhelming, a savage temple which leaves you bowed and humbled in its presence. It is, in a word, sublime.

No one walked these fells for pleasure until the late 18th century. Lakeland was considered a brutal wilderness that was to be shunned. As Norman Nicholson puts it in his book The Lakers, “The seventeenth century saw the mountains as the last defiance of disorder among the colonies of civilisation”. What changed was a shift in aesthetic taste. In 1756, a philosopher named Edmund Burke published A Philosophical Enquiry Inquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, in which he argued that aesthetic sensibilities are underpinned by two fundamental instincts: the instinct for self-propagation and the instinct for self-preservation. Things that are gentle and pleasing and invoke safety or comfort appeal to our instinct for self-propagation, and he called these The Beautiful. Things that are grand or vast and evoke fear or wonder appeal to our instinct for self-preservation, and he called these The Sublime.

The Picturesque movement embraced the Sublime. William Gilpin, Thomas Gray, and William Hutchinson were at the vanguard of a wave of writers who would visit Lakeland and document their experiences in guidebooks— not the route maps and directions of today’s guides, but tour accounts, describing where you should visit, what you should see, even where you should stand. These accounts effervesced with the language of Sublime. They would exaggerate the height of the mountains and describe the towering crags as “terrible”, “awful”, and even “horrific”—all in the literal sense of invoking terror, awe, and excited horror.

Gilpin’s interest may have been superficial, assessing Lakeland scenes in terms of how well they fit the rules of pictorial composition. Gray may have been guilty of viewing much of what he saw in a Claude glass, a small pocket mirror designed to reduce the scene to the proportions of a picture postcard, yet their writing whetted appetites. And they were succeeded by writers who fully embraced this landscape—the Romantics, particularly the Lake Poet, William Wordsworth, who produced his own guide. Hutchinson had dismissed Wasdale as a valley infested by wildcats, foxes, martins, and eagles, and Wordsworth declared that “no part of the country is more distinguished by sublimity.”

The Lakers document this succession of early Lakeland writers. Nicholson looks at the landscape through their eyes and explores how our relationship with it has developed. He concludes that “these modern cults of nature—The Picturesque, The Romantic, The Athletic—are all symptoms of a diseased society, a consumptive gasp for fresh air. They have arisen because modern man has locked himself off from the natural life of the land, because he has tried to break away from the life-bringing, life-supporting rhythms of nature to remove himself from the element that sustains him, in fact, he has become a fish out of nature. The cult of nature in a predominantly urban society is, however, not only a sign of disease; it is also a sign of health—a sign, at least, that man guesses where the remedy might be found.”

Nicholson’s book was published in 1955, the same year Alfred Wainwright produced his first Pictorial Guide. In the strictest sense, Wainwright’s works continue what Nicholson calls the Athletic—the cult of nature that saw the Victorians embrace fellwalking, mountaineering and rock-climbing. Yet Wainwright shared Wordsworth’s romantic vision; his works are much more than physical guidebooks. They are spiritual epiphanies, too. He called the Lakeland mountains “nature’s cathedrals”, and of Scafell Crag, he wrote a paragraph that expresses, better than anything I have read, the wonder and humility of the Sublime:

“A man may stand on the lofty ridge of Mickledore, or in the green hollow beneath the precipice amidst the littered debris and boulders fallen from it, and witness the sublime architecture of buttresses and pinnacles soaring into the sky, silhouetted against racing clouds or, often, tormented by writhing mists, and, as in a great cathedral, lose all his conceit. It does a man good to realise his own insignificance in the general scheme of things, and that is his experience here.”

George Kitching is a columnist for Lakeland Walker magazine, and many of his fascinating Lake District blogs feature on his highly recommended website – Lakeland Walking Tales

Back to top of page